© 2020 Jose Filho

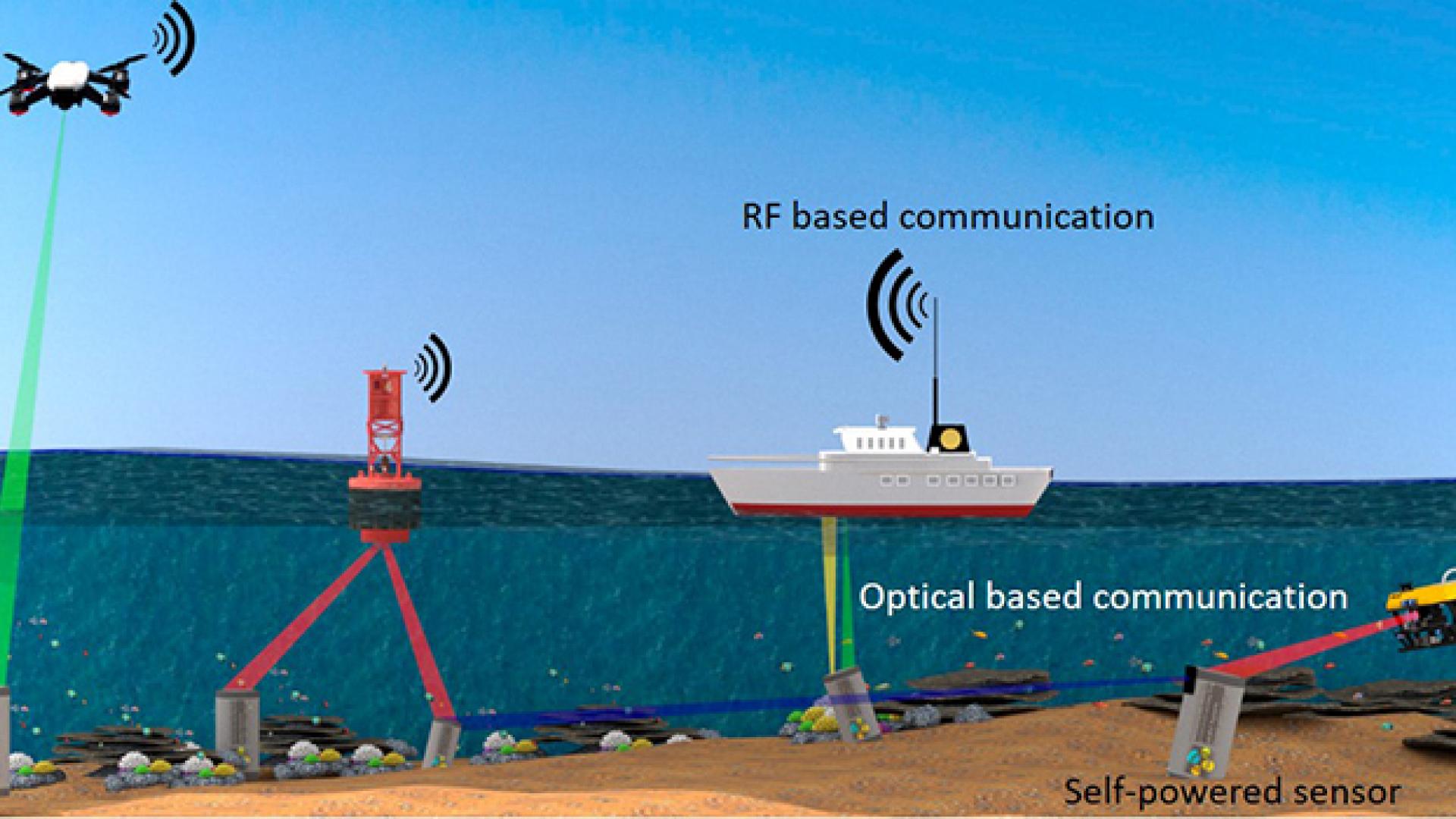

A system that can concurrently transmit light and energy to underwater energy devices is under development at KAUST. Self-powered internet of underwater things (IoUT) that harvest energy and decode information transferred by light beams can enhance sensing and communication in the seas and oceans. KAUST researchers are now solving some of the many challenges to this technology being employed in such harsh and dynamic environments.

"Underwater acoustic and radio wave communications are already in use, but both have huge drawbacks. Acoustic communication can be used over large distances but lacks stealth (making it detectable by a third party) and can only access a small bandwidth," explains master’s student Jose Filho. "Furthermore, radio waves lose their energy in seawater, which limits their use in shallow depths. They also require bulky equipment and lots of energy to run," he explains.

“Underwater optical communication provides an enormous bandwidth and is useful for reliably transmitting information over several meters,” says co-first author Abderrahmen Trichili. “KAUST has conducted some of the first tests of high-bit-rate underwater communication, setting records2 on the distance and capacity of underwater transmission in 2015.”

Led by Khaled Salama, Filho, Trichili and team are investigating the use of simultaneous lightwave information and power transfer (SLIPT) configurations for transmitting energy and data to underwater electronic devices.

“SLIPT can help charge devices in inaccessible locations where continuous powering is costly or not possible,” explains Filho.

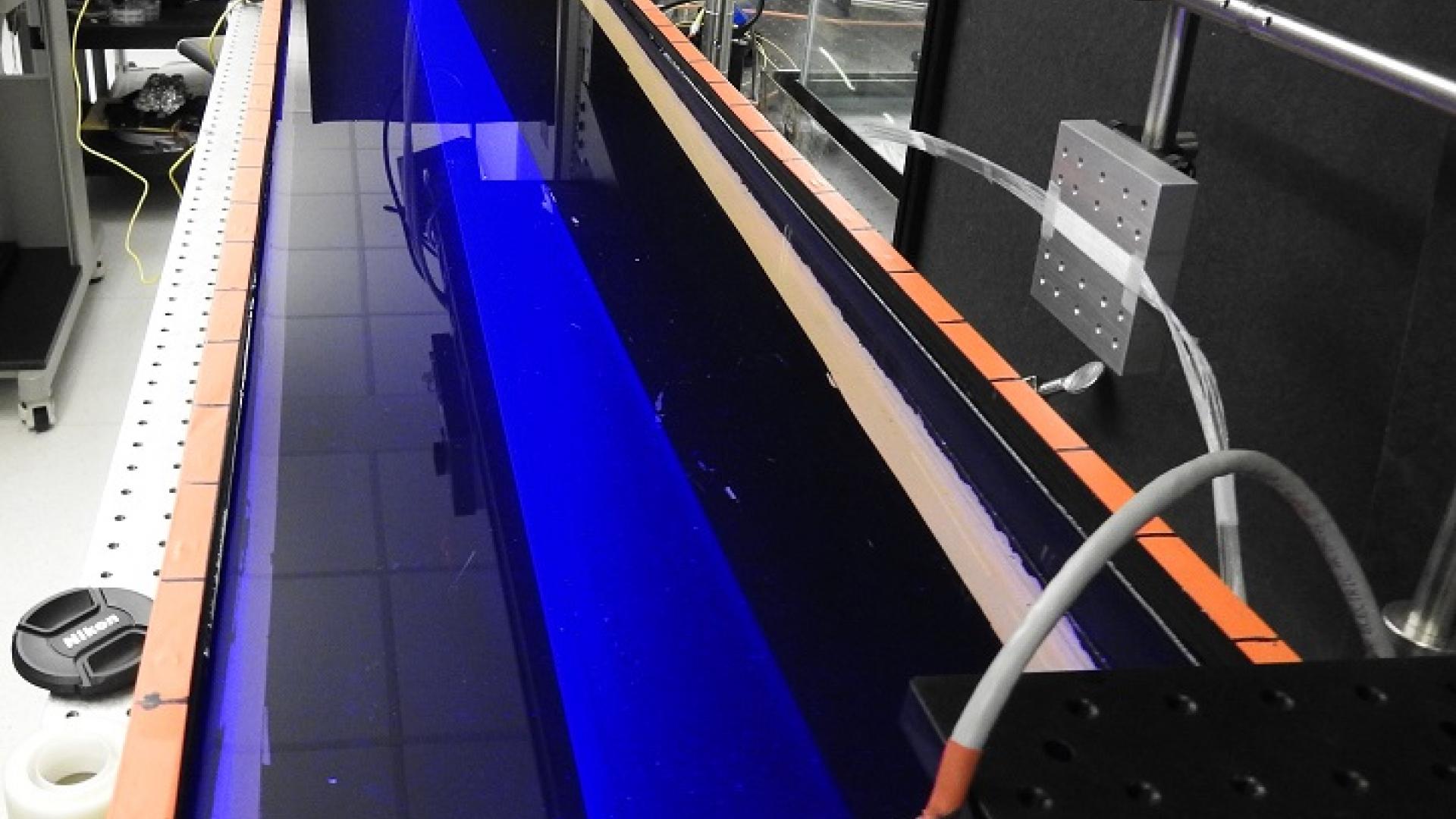

In one experiment, the KAUST team was able to charge and transmit instructions across a 1.5-meter-long water tank to a solar panel on a submerged temperature sensor. The sensor recorded temperature data and saved it on a memory card, later transmitting it to a receiver when information in the light beam instructed it to do so.

In another experiment, the battery of a camera submerged at the bottom of a tank supplied with Red Sea water was charged via its solar panel within an hour and a half by a partially submerged, externally powered laser source. The fully charged camera was able to stream one-minute-long videos back to the laser transmitter.

Read the full article